June is National Indigenous History Month in Canada, when we honour the history and resilience of First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

Gateway partner Centre for Newcomers (CFN) does incredible work to educate immigrants and refugees about Canada’s Indigenous history with its Indigenous Education for Newcomers (IEFN) program, and generously allowed us to repost this article – which was originally published on Jan. 7, 2021 – to help raise awareness about residential schools.

____________________________________

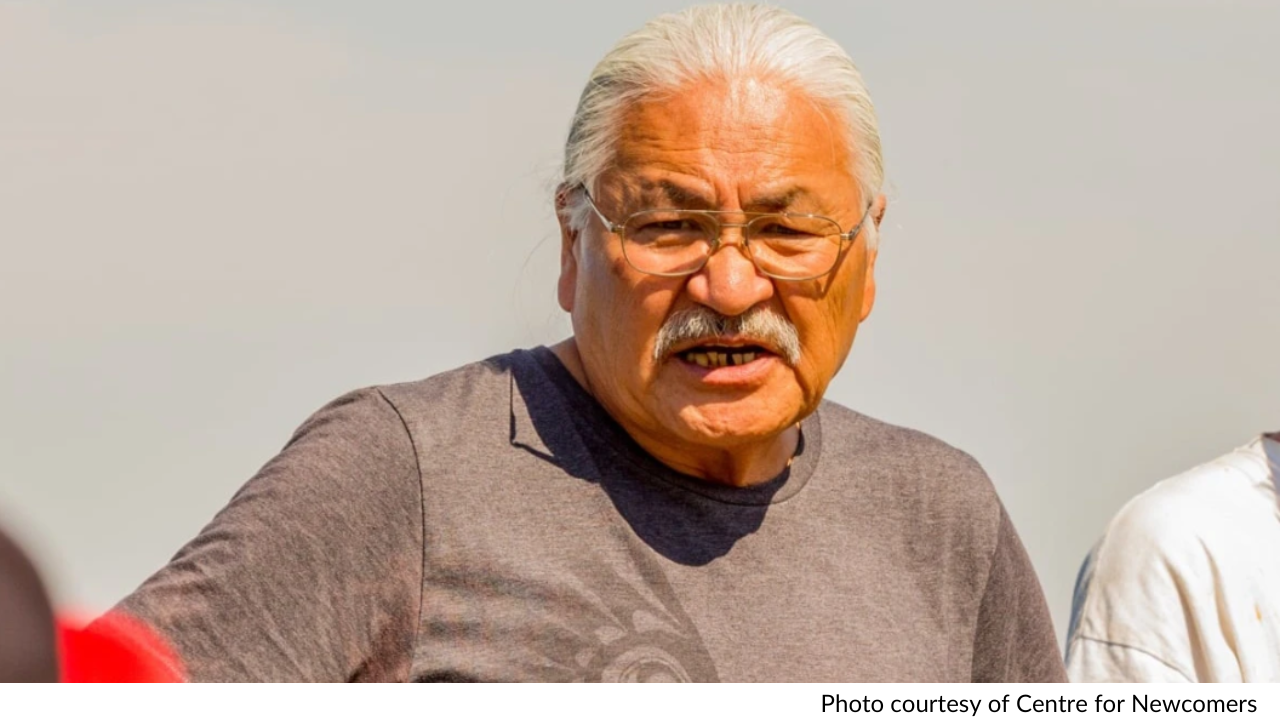

Casey Eaglespeaker, a Blackfoot Elder from Kainai Nation / Blood Tribe, was taken from his family at just four years of age and placed in a residential school. There he would remain until he was 14 years old. Today he is the Aboriginal Resource Coordinator and Traditional Counsellor at Hull Services.

In part 1 of a 3-part series from CFN’s Indigenous Education Program, you can listen to Elder Eaglespeaker talk about the impact of his residential school experience and how residential schools systematically undermined Indigenous culture across Canada, disrupting families for generations, and severing the ties through which Aboriginal culture is taught and sustained.

In 1867, the year of our confederation, Canada instituted a misguided policy of assimilation. The policies in place were designed to be transformative, conditioning Canada’s Indigenous communities to go from “savage” to “civilized”. Indigenous parents, under threat of prosecution from the federal government, were forced to give up their children. Months and even years would pass between time spent with their families, during which time the children were prohibited from speaking their own language, observe their own traditions, or practice their own customs.

The impacts of the residential school experience have been wide reaching and intergenerational. The statement below is from the Manitoba Trauma Information and Education Centre (MTIEC).

“Parents who were forced to send their children to the schools had to deal with the devastating effects of separation and total lack of input in the care and welfare of their children. Many of the children suffered abuse atrocities from the staff that were compounded by a curriculum that stripped them of their native languages and culture. This caused additional feelings of alienation, shame and anger that were passed down to their children and grandchildren. Deep, traumatic wounds exist in the lives of many Aboriginal people who were taught to be ashamed just because they were Aboriginal.

What has also been a significant factor in the healing process of this trauma is that because of colonization the Elders and Healers of the communities, who would have played a vital role in the healing process, were not replaced or were undermined by the missionaries. So what would have provided significant assistance to those who experienced the trauma of the residential schools did not have access to these resources. “Each generation of returning children had fewer and fewer resources upon which to draw” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2012).

The experience of being taken away from their care givers would have been traumatic and had a significant impact on the children’s development. Attachment to a responsive, nurturing, consistent caregiver is essential for healthy growth and development. Many children of the Residential School system did not have this experience after they were taken from their families and subsequently struggle today because of the trauma of being taken away from attachment figures.”

In 2008 the Federal government of Canada established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in order to study and understand these impacts and the tragic legacy of the residential school system. In 2015 the Commission published their report. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

Recent Comments